In support of the Australian Chief Scientist’s #StorytimePledge, we share a post we first published in partnership with Science Book A Day in 2015. Ten excellent books on women in STEMM! After all, you can be a child and read to yourself or share with a child at any age! Immersing yourself in the story of an amazing woman in STEMM makes for inspirational holiday reading. Thanks again to George Aranda for partnering!

Women in STEMM Australia connects women in science, technology, engineering, mathematics and medicine (STEMM) across every professional sector – education, research, industry, academia and government – regardless of their profession.

Our blog aims to highlight the issues, but also to extend the discussion to solutions – how can these issues be addressed? What can we do as individuals, institutes and at a national level? How do we encourage girls to pursue science and retain women in STEMM leadership? We also share personal stories and feature the amazing women in Australian science.

We are active on social media – Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter. So when @PopSciGuyOz, George Aranda, tweeted “Hi there @WomenSciAUST. Would you be interested in doing a list of ’10 Great Books on Female Scientists’? for @ScienceBookADay” – we couldn’t refuse!

We put the call out to women and men across the science sector who are highly motivated to support and promote women in science. On behalf of Women in STEMM Australia, inspiring men and women in science have come together to present our top reads. A few folks dusted off old favourites from the shelf while others shopped avidly online for the latest book in press. Nights were spent avidly turning pages and afternoon coffee breaks spent tapping away on mobile devices. These books are either written by or are about women who have had a major impact on science.

—

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot

My all-time favourite ‘women in science’ book is ‘The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks’. It’s not Australian at all, but I think this is the most important science book I’ve ever read. An essential for those whose role it is to commercialising science. This is a story about the commercialisation of science and the ethical and functional boundaries we need to consider. This is a story about the woman who is the HeLa cell line. Henrietta has contributed to saving the life of millions if not billions of people over time. It’s also a story about equity, race and the critical role of volunteers in science and research.

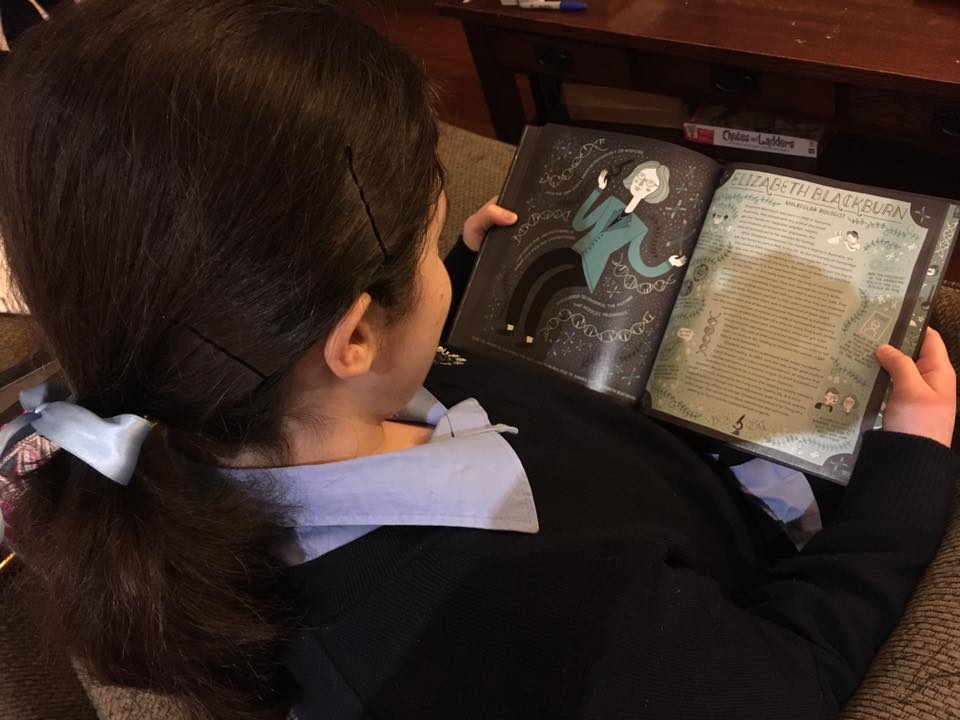

Nobel Prize Women in Science by Sharon Bertsch McGrayne

Nobel Prize Women in Science by Sharon Bertsch McGrayne

At the time this book was written, only 10 women had won a Nobel prize in the sciences among over three hundred recipients. Since that time only 6 more women have joined their rank. Sharon Bertsch McGrayne set out to explore the reasons for the astonishing disparity. She describes the struggles facing women who seek to succeed in science at the highest level and the multiple social and academic barriers they had to surmount. To me, the overwhelming message is that it is indeed a difficult road but that passionate love of science prevails against all odds. Highly recommended reading, especially for those feeling overwhelmed by their current struggles to maintain their career trajectory in the face of multiple other demands. These women are inspirational.

The Door in the Dream: conversations with eminent women in science by Elga R Wasserman

In the preface to this book, Rita Colwell – then president of the US National Science Foundation – asks why women are still so underrepresented in science. The author, Elga Wasserman, had achieved major success in university administration after ‘dropping out’ of science. She started wondering why she had slowly moved out of science and what might have prevented this. To find answers, she decided to consult with women who had established successful scientific careers and had been elected as Members of the US National Academy of Sciences. Her book documents the stories of 26 women, some born early in the 20th century, and others born after the women’s movement started in 1968. Their stories offer widely different insights and describe many factors that contributed to their success, including persistence, good mentoring, talent and luck. They also document the astonishing discrimination they had to surmount, even after 1968. She concludes that what distinguished these women was ‘their phenomenal passion, drive and persistence….they dared and they took risks. Each found a way to deflect negative messages without losing her bearings.’

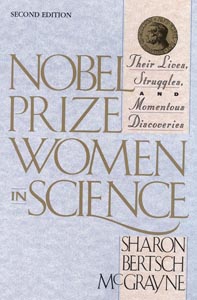

A Feeling for the Organism: The Life and Work of Barbara McClintock by Evelyn Fox Keller

A Feeling for the Organism: The Life and Work of Barbara McClintock by Evelyn Fox Keller

Barbara McClintock (1902-1992) was an American scientist. She received her PhD in botany from Cornell University in 1927, for a thesis on the cytology and genetics of maize, and this topic was the focus of her research for the rest of her life. She made many important discoveries with very broad applicability, some of which were met with deep skepticism by other scientists. Later research confirmed her discoveries, and she was awarded the 1983 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Three aspects of her life and work stand out. Barbara McClintock was a woman, and she faced what we might call the usual challenges that women scientists in the mid-20th century met, e.g. her alma mater Cornell would not hire a woman professor. She definitely did not like this. Also, she had an individual way of doing science, one very different from the way others in her field went about their research. She took pride in calling herself a mystic. The title of the book hints at this. Finally, McClintock’s career was affected by what one might think of as an historical accident. Her research was initially in the mainstream of genetics – she was elected President of the Genetics Society of America in 1944 – but she was to become marginalized with the rapid growth and enormous success of the new field of molecular biology. It took a long time for a molecular understanding of her most important work to emerge. As a woman, as someone with a very personal way of doing science, and as a scientist making discoveries that did not make sense under the dominant paradigm, she had a very hard time. This fascinating book discusses all these aspects of her life, and puts them together in a compelling and sympathetic portrait of a remarkable woman.

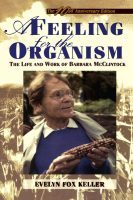

In Praise of Imperfection: My Life and Work (Sloan Foundation science series) by Rita Levi-Montalcini, translator Luigi Attardi

In Praise of Imperfection: My Life and Work (Sloan Foundation science series) by Rita Levi-Montalcini, translator Luigi Attardi

Rita Levi-Montalcini (1909-2012) was an Italian neurobiologist. Although initially discouraged from attending university by her father, she persuaded him to let her study medicine and graduated with an M.D. in 1936. In 1952, working in the U.S.A., she completed her most important work, co-discovering the nerve growth factor NGF. For this she shared the 1986 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

This moving autobiography tells the story of a Jewish woman growing up in Fascist Italy. Levi-Montalcini writes poignantly about her family, her youth, her schooling, and how, after Mussolini’s race laws prevented her from having a position in a university, she was inspired by the Spanish neuroscientist Santiago Ramón y Cajal to set up a bedroom laboratory in her family home. She shows us how she made her life as she wanted it to be, writing “My experience in childhood and adolescence of the subordinate role played by the female in a society run entirely by men had convinced me that I was not cut out to be a wife”. We learn how she was invited to Washington University in St Louis, Missouri for a short stay and remained for nearly 20 years. A visit to Rio was critical in her quest for the NGF, and her later success together with Stanley Cohen. She speaks of this as ”one of the most intense periods of my life in which moments of enthusiasm and despair alternated with the regularity of a biological cycle.”

Explaining her title, she writes “It is imperfection – not perfection – that is the end result of the program written into that formidably complex engine that is the human brain…” This is the compelling autobiography of a fiercely independent, creative woman scientist, and is an inspiration to us all.

Dorothy Hodgkin: A Life by Georgina Ferry

Dorothy Hodgkin: A Life by Georgina Ferry

This is a book full of warm human detail, giving a marvellous insight into the life of an incredible scientist who rewrote the rules for women in science. Born in Egypt to English parents in 1910, Dorothy Crowfoot, later Hodgkin led anything but an ordinary life. As a young girl she saw very little of her parents, who were often away on archaeological digs. Her extended family was female dominated, because many of the men were killed in the Great War. At Oxford as an undergrad student, she was obsessed by crystals and chemistry. This continued through into her PhD studies at Cambridge under the great JD Bernal, with whom she published the first evidence that protein crystals diffract X-rays. Her own independent research at Oxford University/Somerville College was devoted to the chemistry and structure of key biological molecules: vitamin B12, penicillin, insulin, amongst others. Dorothy by all accounts was brilliant, unconventional, disorganised, and much-loved. Awarded the 1964 Nobel Prize in Chemistry – the news arriving when she was in Ghana with husband Tom – she used part of the prize money to establish a nursery at Somerville College.

For crystallographers, “Dorothy Hodgkin: A Life” is a treasure-trove of tales from and about giants in the field including antipodeans: Dodsons, Bakers, Cutfields, Mackays. For anyone, it’s a terrific read, an inspirational read, with life lessons abounding – not least the “prescription for women’s success in science” in the last few pages, attributed to another great crystallographer Kathleen Lonsdale.

Three other quotes that resonate still:

- “There was a magic about her”

- “If Dorothy’s life has anything to teach us, it is that there is an alternative approach”

- “Scientists have a role in shaping society”

Headstrong; 52 Women Who Changed Science and the World by Rachel Swaby

Headstrong; 52 Women Who Changed Science and the World by Rachel Swaby

Educate women and risk underdeveloped ovaries. This amusing 19th century argument was laid to rest by scientist Mary Putnam Jacobi in 232 pages of numbers, charts and analyses. Jacobi is the first of 52 women surveyed by author Rachael Swaby. Each is distinguished by tenacity and rigour, with a number working for no pay or reduced status in order to pursue a career in science. And we are fortunate they did. Their results include Kevlar, wrinkle free cotton, assessment tools for newborns, arc lighting, frequency hopping communication, treatments for leprosy and fundamental principles about the metabolic system.

Do women scientists need a book of their own? Until such time as they do not, Swaby’s accessible tales offer a captivating blend of tragedy, comedy, achievement and inspiration.

Rosie Revere, Engineer by Andrea Beaty

Rosie Revere, Engineer by Andrea Beaty

Kindling for the dreams of young engineers and inventors, girls and boys.

Curie by Sarah Dry

Marie Curie is surely one of the great pillars of twentieth century science. She was not only the first woman to be awarded a Nobel Prize in 1903 (at the young age of 36), but she followed this with a second Nobel Prize in 1911. Curie and her husband Pierre were the first to show that radioactivity was an atomic property. Curie fought constantly to be recognised within a male-dominated society. Initially the Nobel committee had considered only awarding the 1903 Nobel Prize to Pierre alone and it was only at Pierre’s insistence that Curie was included. This is tempered by the fact that these studies were initiated by Curie and it was only later that Pierre became involved. One of the most memorable photos included in this book gives some impression of the magnitude of her achievements within society at this time. It shows Curie at the inaugural invitation-only Solvay conference held in Brussels in 1911 where she is the only female among 29 eminent scientists including Einstein, Bohr, Schrodinger and Pauli.

This highly-readable book succinctly follows Marie Curie’s life. From her early childhood in Poland under the oppressive rule of the Russian Tsar, her long and highly productive scientific career, through to her final years eventually succumbing to the effects of long-term exposure to radiation at the age of 67. She made pioneering discoveries in the field of radioactivity, with discovery of two radioactive elements Radium and Polonium (named after her country of origin) and spent the later years of her life pioneering the use of radiation in medicine and many other fields. These hard-won discoveries (taking 3 years to extract one-tenth of a gram of pure radium from several tonnes of ore) were complemented by periods of joy, such as the births of their two daughters Irène and Eve, and tragedy (the untimely death of Pierre when Curie was 39). The final chapters of this book provide a short biography of Curie’s eldest daughter Irène, who followed in her mother’s footsteps and was awarded the 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry along with her husband Frédéric Joliot for the synthesis of new radioactive elements.

Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA by Brenda Maddox

Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA by Brenda Maddox

The Dark Lady of DNA is one of the few books that shed light on the story of scientist Rosalind Franklin – most well know because of the controversy around her role in the discovery of the structure of the building blocks of life, DNA. The biography written by Brenda Maddox takes the reader on a journey from Rosalind’s upbringing in England, her move to France where she gained training in the scientific technique x-ray crystallography and back to the Kings College in London where using x-ray diffraction she took the image of DNA referred to as photo 51. It is this photo that led to the discovery of the double-helical structure of DNA however most of the credit to this scientific discovery went to male scientists James Watson, Francis Crick and Maurice Wilson who went on to be awarded the Noble Prize in 1962. Dying of Ovarian cancer in 1958 at the young age of 37, Rosalind was ineligible for this prestigious prize. This biography is must read for anyone interested in history, scientific discovery and the challenges facing women in an often-considered male career

Boyer Lectures 2014: The Promise of Science – a vision of hope by Suzanne Cory

Boyer Lectures 2014: The Promise of Science – a vision of hope by Suzanne Cory

Each year the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) invites a prominent Australian to present the Boyer Lectures, and the 2014 transcripts that comprise this easy-to-read book were written by one of Australia’s leading women in science, Professor Suzanne Cory. Cory is a world-leading researcher in cancer genetics and was the first woman elected President of the Australian Academy of Science. Cory takes you on a journey that has both a historical bent and a present day modernism that engages the reader. She writes with warmth and sincerity about the promise of science for Australia and what is has done – and will still do – for the broader community, our nation’s economy and for the world’s health. Cory speaks with a unique perspective, as a leading woman in science who is internationally recognised for her ground-breaking cancer research and her contribution to science education and public policy. With few women reaching this level of success in science, Cory speaks with passion about the support and encouragement she had throughout her career, and the need for change across the scientific sector to allow more women to become leading researchers and innovators in their own right. An inspiring read for all ages – scientist or not!

Together, we can do amazing things. If you identify as a woman in STEMM, or you champion change in STEMM, then Women in STEMM Australia is for you. Join this important discussion and learn more about the phenomenal women in STEMM Down Under!

Thank you very much for sharing this. Great books to read during quarantine. Is these books are available to read online on amazon kindle?