Over 40 years ago Syd Leach started a small meeting in the Victorian seaside town of Lorne. The “Lorne Conference on Protein Structure and Function” has grown to become Australia’s largest protein-focused meeting, typically featuring talks from approximately 18 leading invited scientists from around the world.

Was this a problem? We were getting great speakers, the meeting was always well attended, and program feedback was good. Were we unconsciously settling into a culture of “Why fix what is not apparently broken?”?

None of us could avoid the uncomfortable feeling that we were not being fair. Numerous studies reveal equal numbers of male / female life scientists at the early career stage, with a rapid drop-off of women in more senior positions, where female life science professors are often very poorly represented. Maybe a paucity of senior female researchers was genuinely a reason behind our speaker imbalance, but all we were doing was continuing to perpetuate the issue.

Actions speak louder than words

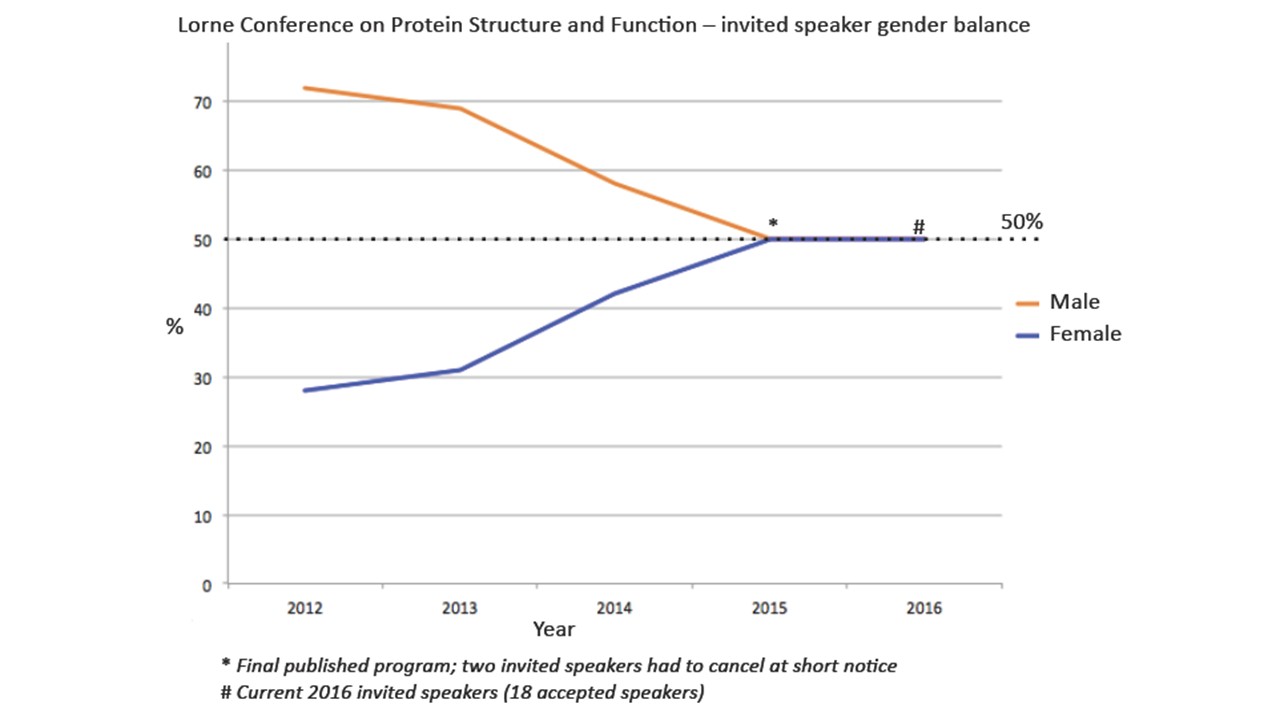

In 2012 we wondered what would happen if we changed our policy and simply invited more women, while maintaining our high standards of speaker quality. There were no arguments - after all we could simply abandon the policy if it didn’t work. We further actively ensured we maintained gender equity in our organising committee, for our session chairs and for selected abstract talks – if you are interested in how the latter works, we simply check that we maintain the gender balance of applications and selected talks.

The initial impacts were striking and not quite what we expected.

The policy gave the committee a new challenge to rise to – and members seemed invigorated by it! While we always did our collective best to feature new speakers, almost all conference committees after a while unconsciously tend to suggest “old favourite” speakers. These tended to be low risk individuals who could be relied on to turn up and stay for the whole meeting, who always gave great talks and who were invariably popular with delegates.

Unexpected benefits

With our new policy a greater number of wide ranging discussions opened up around speakers we had never considered before. Committee members became more forward thinking when it came to seeking the best speakers and would regularly return from international conferences with new names and exciting new scientific directions to feature. Once we started thinking in this way, we found it was surprisingly easy to identify established senior female scientists for our programs, and the committee unanimously updated our policy, from just “invite more women” into “invite equal numbers of male and female speakers”. No arguments about what proportions are reasonable - nine male and nine female speakers – simple!

The committee also started to suggest and endorse many more outstanding early-to-mid-career female scientists as speakers. A natural extension of this was to also consider more male up-and-coming scientists. In the past, these individuals could miss out on a speaking spot as the committee would worry that they would be less of a “draw” than a very senior scientist. This concern was alleviated by our delegate feedback - while some aspects of the meeting always remained predictably contentious (quality of lunches and internet speed being two examples we have repeatedly but unsuccessfully tried to fix) - we received improved and enthusiastic endorsement of the scientific content of the meeting.

Indeed, many of the presentations by the younger speakers we featured, both male and female, started being highlighted as standouts in delegate feedback. Our very simple gender policy changes were having a much broader impact on early- and mid-career researchers.

Staying on track

Our policy on improving and maintaining gender equity is now entering its fourth year – we maintain statistics on our website. As any organizer knows, a conference will always lose some speakers at the last minute, so sometimes despite our efforts we still sometimes end up with an apparently skewed program. In 2013 for example two of our female speakers had to pull out because of the February Nor’easter grounding planes out of the US. We do find that women with young families find it harder to travel. But if they can’t make it we invite others – and reissue the original invitations a year or two down the track.

To make things a bit easier, in 2016 we are offering a few bursaries to help with child care-related travel; this initiative was suggested and initially funded by the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, and subsequently has been supported by multiple local institutions and universities.

To make things a bit easier, in 2016 we are offering a few bursaries to help with child care-related travel; this initiative was suggested and initially funded by the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, and subsequently has been supported by multiple local institutions and universities.

Would we abandon the policy and go back? No! By challenging ourselves and setting a gender equity policy, we feel we have invigorated the meeting through better representation of early and mid-career researchers and more diversity of topics and that the meeting is more exciting than ever before.

*****

Jacqui Matthews is the Professor of Protein Chemistry at the School of Molecular Bioscience at the University of Sydney, Australia. She uses structural biology, biophysical and molecular biology approaches to unravel the intricacies of protein-protein and protein-nucleic acid interactions in gene regulation. She also seems to spend a lot of time on conference organising committees asking people to put forward names of more female speakers. Jacqui really enjoys her current role as Vice-president and Program Chair of the Lorne Conference for Protein Structure and Function where her colleagues do this without any extra prompting.

Jacqui Matthews is the Professor of Protein Chemistry at the School of Molecular Bioscience at the University of Sydney, Australia. She uses structural biology, biophysical and molecular biology approaches to unravel the intricacies of protein-protein and protein-nucleic acid interactions in gene regulation. She also seems to spend a lot of time on conference organising committees asking people to put forward names of more female speakers. Jacqui really enjoys her current role as Vice-president and Program Chair of the Lorne Conference for Protein Structure and Function where her colleagues do this without any extra prompting.

James Whisstock is Director of the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence in Advanced Molecular Imaging and an NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellow. His teams’ research program covers bioinformatics, structural biology and molecular genetics, with a particular focus on infection and immunity. Recent discoveries include the structure of the immune effector perforin and the structure of plasminogen, the latter protein being an important part of the fibrinolytic cascade. James has a particular interest in applying new technology to biological problems. Most recently he and his team established the Clive and Vera Ramaciotti Centre for cryo-electron microscopy (EM), a high end EM platform for studying the structure of challenging proteins.

James Whisstock is Director of the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence in Advanced Molecular Imaging and an NHMRC Senior Principal Research Fellow. His teams’ research program covers bioinformatics, structural biology and molecular genetics, with a particular focus on infection and immunity. Recent discoveries include the structure of the immune effector perforin and the structure of plasminogen, the latter protein being an important part of the fibrinolytic cascade. James has a particular interest in applying new technology to biological problems. Most recently he and his team established the Clive and Vera Ramaciotti Centre for cryo-electron microscopy (EM), a high end EM platform for studying the structure of challenging proteins.